April 2015

Sea lion research on the Washington Coast

Adrianne Akmajian, M.Sc. student

18 April 2015

I began working on the Washington Coast in 2011 when I moved to the town of Neah Bay to work for the Makah Tribe. On the tip of the Olympic Peninsula, Neah Bay is located at the point where the Pacific Ocean joins with the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which eventually flows into the inland waters of the Salish Sea. There are several major haulout sites on the Washington coast that are used by both Steller sea lions and California sea lions throughout the year.

Steller sea lions near Tatoosh Island, WA (Photo: Adrianne

Akmajian)

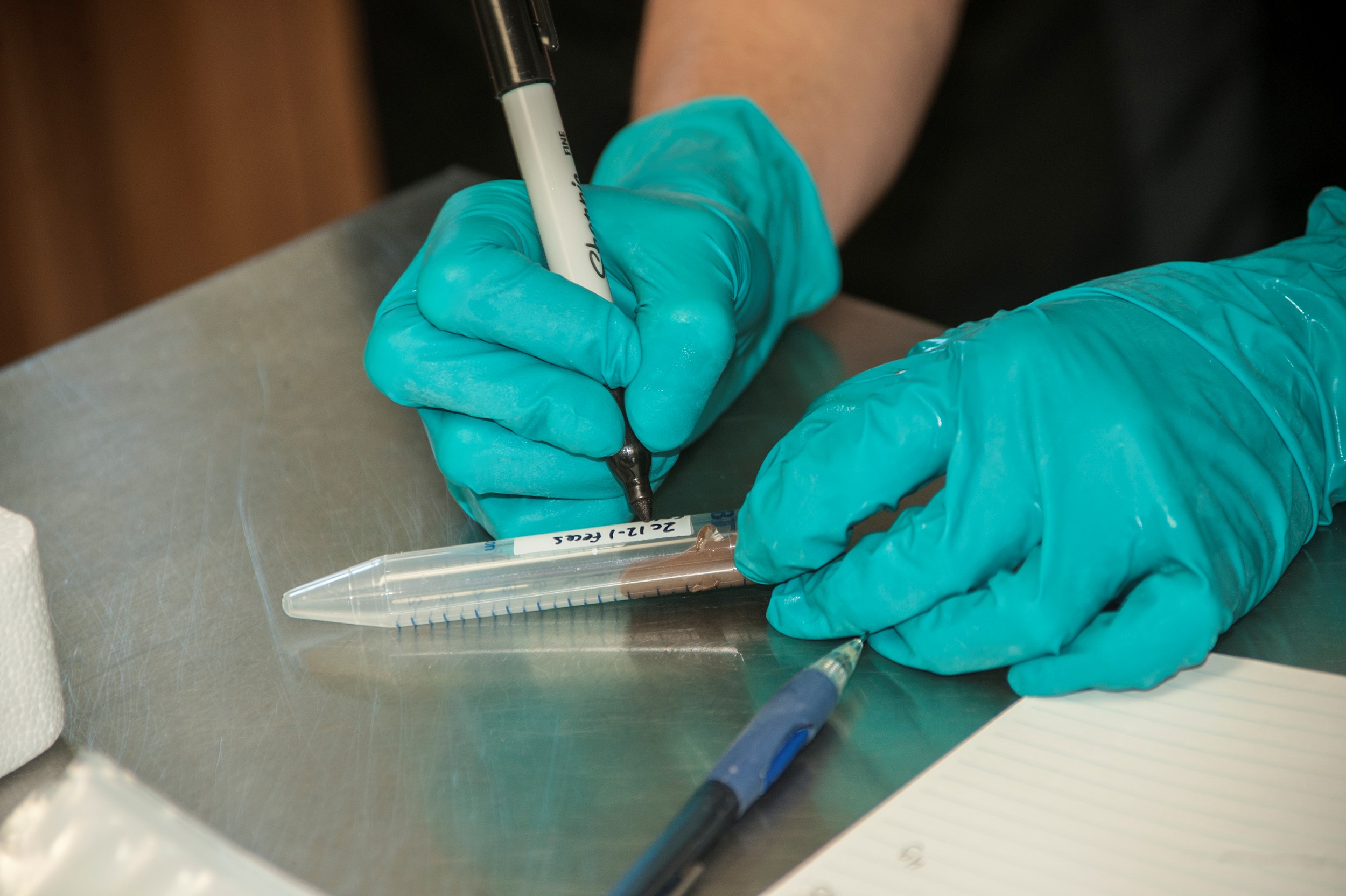

A major project I worked on was studying the sea lions’ diet to see what they eat throughout the year. The easiest way to study what an animal eats it through its poop! So, I spent the better part of two years collecting sea lion scat (>1000 samples!) and washing and picking out fish bones and octopus or squid beaks. Through this diet project, I began a side study that has since become the focus of my thesis research.

Sea lion scat, Bodelteh Island, WA (Photo: Adrianne Akmajian)

Scat collection, Tatoosh Island, WA (Photo: Doug Sternback)

I began taking subsamples from many of the scat to look at whether or not the sea lions are exposed to marine algal toxins. Marine algal toxins, frequently referred to as “red tide”, are toxins produced by phytoplankton. Large blooms of the phytoplankton lead to high and dangerous concentrations of the toxins that cause several types of shellfish poisonings in humans. I have focused on two algal toxins that are common on the Washington coast: domoic acid (which causes amnesiac shellfish poisoning in humans) and saxitoxin (which causes paralytic shellfish poisoning).

Marine algal toxins also cause illness and death in marine mammals. Probably best known on the US West Coast is the case of California sea lions dying from domoic acid poisoning. My study will be the first to document sea lion exposure to these two algal in Washington sea lions.

Scat subsample to be analyzed for marine algal toxins (Photo:

Debbie Preston)

Harbor seals in downtown Bellingham

Ashlyn Teather, undergraduate student

17 April 2015

Hello, my name is Ashlyn Teather! I am an undergraduate senior here at Western and will be graduating this quarter (June 2015). I am actually a part of Huxley College, and will be getting my degree in Environmental Science, with a minor in Environmental Education. I am from Camano Island, which is just about 40 minutes south of Bellingham. So, the Pacific Northwest has always been near and dear to my heart. Applying for college was an interesting and intimidating time of life, but am happy that I ended up at WWU.

What drew me to Environmental Science is a wonder and curiosity I have always had of my immediate surroundings. I am particularly interested in the idea of conservation, especially in this time of the so-called Anthropocene where loss of biodiversity is a crushing reality we face every day. Even further into this, I am interested in wildlife conservation. Additionally, I am minoring in Environmental Education. I think reaching out to society, and especially getting children interested in nature is important. One of my jobs outside of university is nannying a nine-year-old girl. I am continually impressed by her knowledge and creativity and think children really have the capacity to understand more than we think. As cliché as it may sound, “kids these days” are our future, and teaching them about nature, and how to think critically, will be most valuable.

Coming to work in Alejandro’s lab happened by chance for me because a friend of mine previously headed this undergraduate project last year and asked if I wanted to assist him in counting seals. Now this year I am heading the project and am pleased with the opportunity to do so. My project looks to monitoring the number of seals that haul out or swim in an area known as the Log Pond in Downtown Bellingham. Monitoring these seals is of interest because the Log Pond is a part of an area known as the Waterfront District which the City of Bellingham is planning on redeveloping. The area will go from a private industrial site to a more public commercial and recreation area in the coming years. This research projects seeks to find out if redevelopment, leading to more public access in the vicinity of the seals, will have any effects of their numbers or preferred haul out location. However, similar to Sara, I will talk more in detail about my project in another post!

One thing that draws me to work with Alejandro is his interest in science education as well as the hard science of marine biology. Immersing more students in the STEM fields when they are in high school, and even before that, is important. I hope in my (not so distant) post-grad future to head off into a path that involves me conducting more research, but then also working with children in education.

Thanks for taking the time to read a little bit about me! Stay tuned for more information on my research in the following months.

The importance of an undergraduate research experience

Allegra La Ferr, undergraduate student

16 April 2015

When I asked my professors as a sophomore in college, what I could do to prepare myself for graduate school and a future career in the sciences, they all said the same thing. Get research experience. After asking around, I landed myself a spot in the Marine Mammal Ecology Lab.

I've had many friends say things along the lines of "That would be so cool to be a part of!" Or "How did you get involved in that?". The answer is simple, just ask! I've found that if you are willing to take the first step, most professors are more than happy to talk with you about their research, and what is currently going on in their lab.

Ive been a member of the Log Pond project for a year now (look for a more detailed post on the project soon!) and the experience I've received has been invaluable. During my year I've learned practical things such as current methodologies in marine mammal research or how to design a scientific poster. But i've also gained hands on experience, assisting with harbor seal necropsies, attending scientific conferences and even grinding up salmon to help another graduate student. Currently, i'm learning how to use bioacoustics software to assist Kat on her graduate work. As you can see, I've been able to participate in many different aspects of science research. While these kinds of opportunities are certainly available outside a research lab, being a member of the lab means having regular access to these types of learning opportunities.

Additionally, being part of a research lab as an undergrad has given me insight into what graduate school will be like. It has given me the opportunity to learn about the finances of graduate school, grant writing, the intricacies of publication, writing a thesis, and being a TA. It has been great to form connections with my professor, the graduate students and the other undergraduates. I would highly encourage other undergraduates to participate in undergraduate research. Not only for the sake of putting it on your resume, but to gain insight into the "real" world of science outside the classroom.

How I became involved in research

Sara Spitzer, undergraduate student

14 April 2015

Hello, my name is Sara Spitzer and I’m currently a senior undergraduate student working in Alejandro’s lab. I will graduate Fall 2015 with a BS in Molecular and Cell Biology. I was born on the east coast of the US and moved to Southern California when I was 11 and have lived there ever since. I decided to attend Western because a professor I was completing an internship with in high school said it had fabulous research opportunities for undergraduates and I’ve found that to be completely true.

I’ve always known that I wanted to be a biologist. In fact, as soon as I could grasp the concept of marine biology at a ripe old age of five, I was certain that’s what I wanted to pursue. There is an unfortunate stereotype that people who want to be marine biologists only want to swim with and/or train cuddly ocean megafauna, but this wasn’t true for me. I was just as happy learning about tube worms, algae, and bacteria as I was about dolphins, turtles, and seals. When I started at Western, naturally I was a Marine Biology major. Over time, though, my interests changed. I took my first cell biology course (BIOL 205) and fell head over heels in love with it. I debated changing majors but decided against it because I was so convinced that I wanted to study marine science. I was afraid of what changing my major would mean. What if I didn’t like it? What would I do with my life then? By that point I had spent the majority of the last 18 years of my life planning to be a marine biologist and I didn’t know how to incorporate cell biology into my plan. So I kept chugging along through the marine major until I took the upper division Molecular and Cell Biology course required of all biology majors and I found that I still was deeply enthralled by cellular processes. I finally decided, in the middle of my junior year of course, that I would be happiest if I studied biology at the molecular level. Officially turning in the paperwork to change my major was a wonderful feeling, especially after so much internal debate and anxiety. I knew I’d made the right decision.

At this point, I was already signed up to take the study abroad Tropical Marine Biology course in Mexico during that summer and I thought it might not be as applicable to my major now that I was not longer marine. However, both of the big projects I completed involved genetics and molecular lab techniques. It was a truly amazing experience that I will write about in a different blog. After the Mexico class, I thought I was departing from marine science until I Alejandro contacted me. He was one of the professors who came with us to Mexico and he noticed I was enthusiastic about genetics. So when he and Dietmar were looking for someone to take over a project involving seal genetics, he asked if I would be interested. Of course I said yes! So here I am, using genetics to study marine mammals! I’ll tell you more about my research in another blog post.

I guess the point I’m trying to make is that no matter how dead-set you think you are on a certain path, you may find that there is something else you like better. Do what feels right for you, even if it’s different from what you planned. And you may even end up incorporating your old love into the research centered around your new love. That’s a pretty cool feeling.

Fieldwork part 1- The beginning

Kat Nikolich, M.Sc. student

7 April 2015

Many people seem to think that the life of a marine mammal ecologist is nothing but swimming with dolphins, tackling seals and following whales around. And for many of us, that’s definitely a perk of the job. However, for every research project I’d estimate that only 10% of the researcher’s time is spent on field work. However that 10% is what made me (and every child, for at least a hot second) want to study marine mammals. Maybe I’ll write about the other 90% later, but for now, I’m going to entertain you with stories from the field work that I underwent for my Master’s project here at WWU.

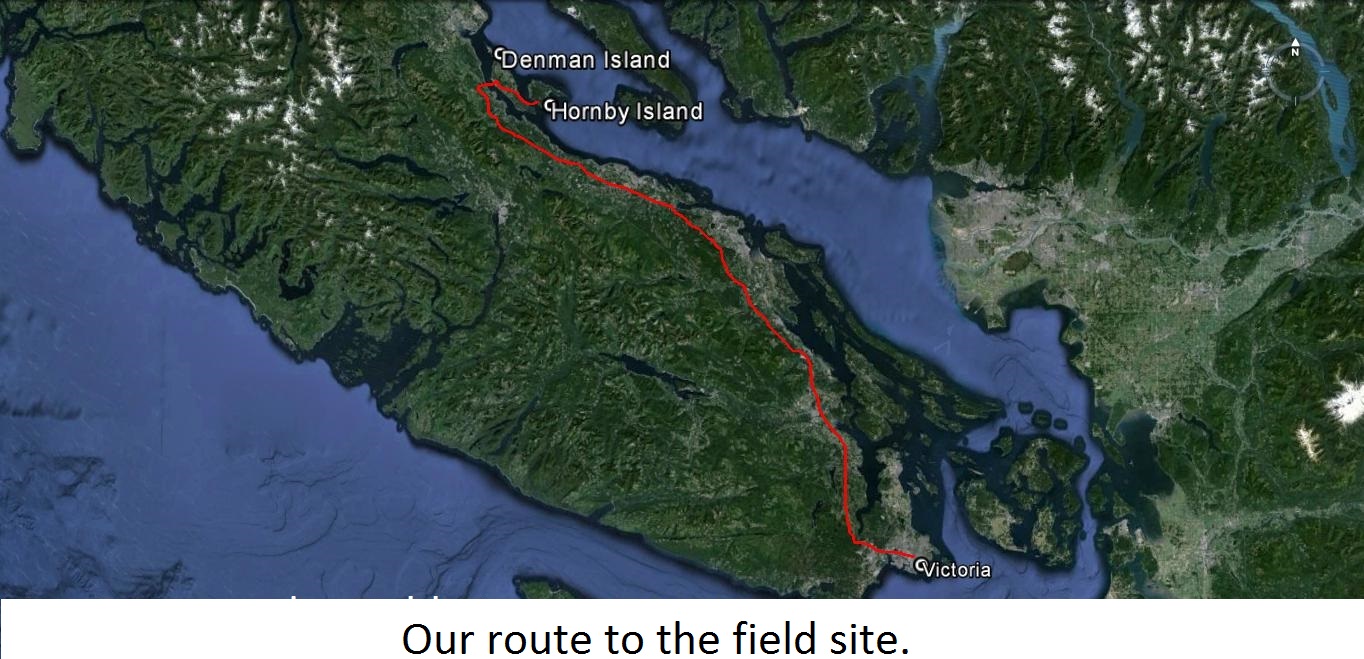

Six weeks of my summer 2014 were spent in the beautiful Northern Gulf Islands of British Columbia, Canada. My field site was located on the south shore of Hornby Island, the outermost of the Northern Gulf Islands. I took three separate two-week trips out to Hornby to observe the harbour seals I was recording with my hydrophone. I was accompanied on each trip by three intrepid undergraduates or recent graduates from WWU. There are many tales to tell, and my interns would be upset if I missed any of the highlights, so I’ll tell the whole story in a multi-part epic. My next several posts will detail all of my field sessions, starting with our first journey to the field site and deployment of my hydrophone and recording equipment.

The first field session started on the Sunday after exams finished for the year. I met my first-session interns, Kayley, Kayla and Erin, at the ferry terminal in Victoria the night before. In the morning, we packed my father’s aging Nissan Pathfinder to the hilt with equipment, food, camping supplies, personal effects and a very cramped trio of undergrads (as the driver, I was the only one not required to sit on anything, nor have anything placed at my feet or on my lap). After a claustrophobic three-hour drive north in the teetering SUV, we arrived at the second ferry terminal of the trip. For the few hundred people that make the Northern Gulf Islands their home, the glorified barges of the BC Ferries northern fleet are a necessary way of life. We arrived just in time to see the ferry departing, and we had to wait an hour and a half for the next scheduled sailing. While we waited, we browsed the terminal amenities, which were limited to a gas station that boasted a convenience store and a Subway. After finally making the ten-minute crossing to Denman Island, we embarked on what I came to know as the Denman Dash – a sprint to the long, thin island’s opposite end, where another ferry would carry us to Hornby Island. Along with the rest of the ferry traffic, we darted at an imprudent speed over the bumpy, unkempt road to the next terminal in time to catch the ten-minute ferry to our final destination.

If you’ve ever visited an island in the Pacific Northwest, then you’ll probably understand that life there is a bit different from life on the mainland. Populated mainly by wealthy retired folks, artists, organic farmers and Westfalia-inhabiting transients, the islands are a bastion of days long past, when life was simpler and everything was done by hand (that’s the romantic version, anyway). Islanders are fiercely protective of their lifestyle, and can be seen as reclusive, elitist and resistant to change. Once you get to know them, however, they are some of the most genuine, resourceful and hospitable people I have ever had the pleasure to work with. Our first sight of Hornby Island upon disembarking from the ferry was a sign taped to a tree that declared ‘Free Jazz Every Friday’, and pointed to a slightly dilapidated building with a thatched roof that sported the island’s only pub (which also serves as a restaurant, marina, coffee shop and liquor depot). The second sight was another sign, which enigmatically argued ‘No Coal Mines’.

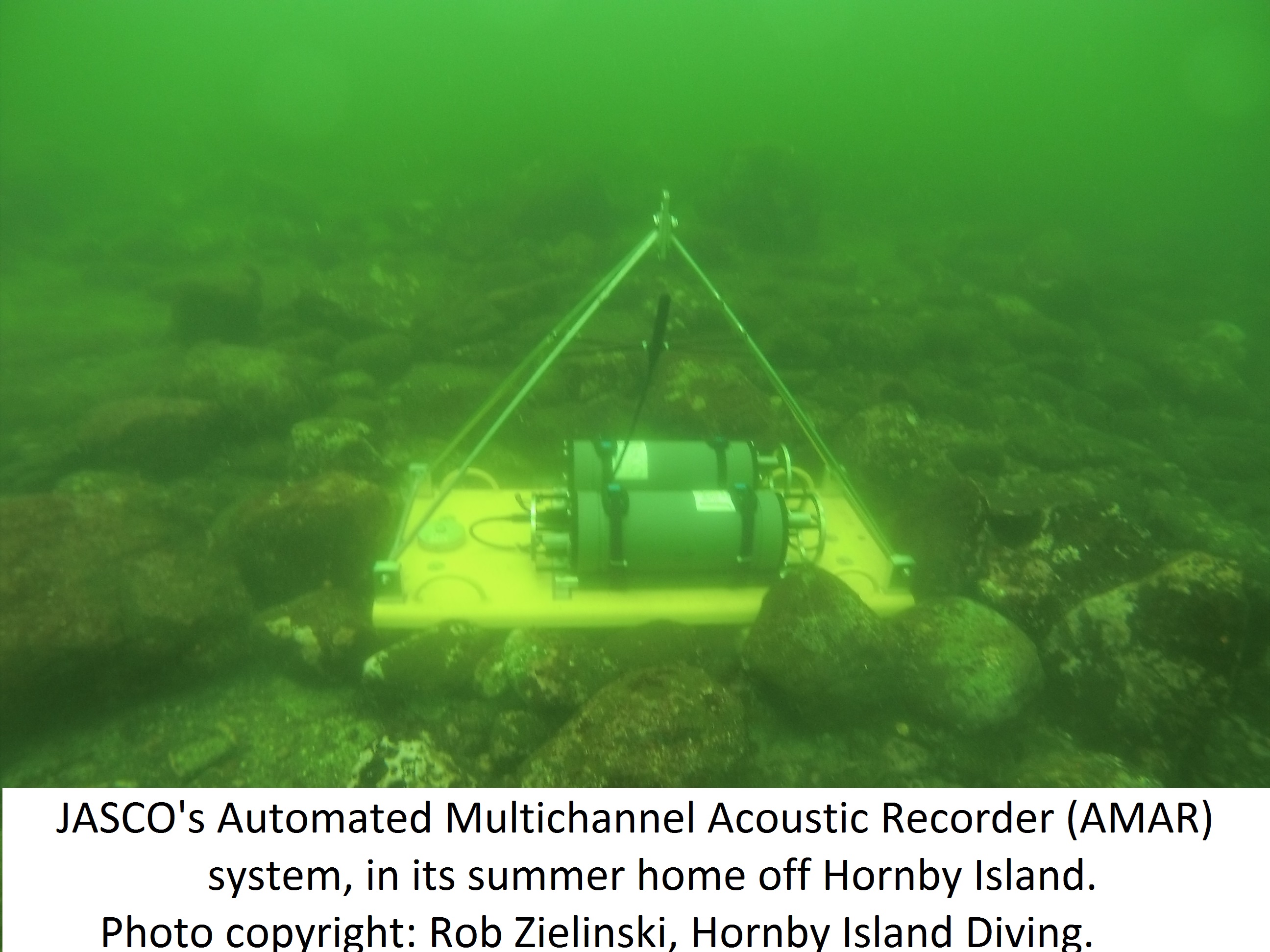

Our first order of business was to deploy the hydrophone and recording device that would collect acoustic data on the harbour seals throughout the summer. We drove straight to Ford’s Cove marina, which was to be our base of operations, and met up with our ground crew. I maneuvered the overstuffed SUV into the driveway of Rob and Amanda Zielinski, the owners of Hornby Island Diving. Rob’s family have lived on Hornby all his life, and he and his wife Amanda are one of the main reasons I chose it as a field site. A former colleague of mine had introduced us months before, and the Islander couple had graciously given me all the help and information I needed to set up my project.

Because my hydrophone equipment was on loan from JASCO Applied Science, they had sent an acoustics expert to help with the deployment. Xavier Mouy immigrated to Canada from his native France to pursue a graduate degree in Quebec, and has worked for JASCO for eight years. His wife, Heloise, also works for JASCO and is a member of my thesis committee. As Heloise was preoccupied by being nine months pregnant at the time, Xavier was sent to help out. Rob helped us haul the 70-pound hydrophone rig to the dock, and the six of us (Rob, Xavier, myself and the three assistants) hopped onboard the Zielinski’s dive charter boat for the short trip out to the deployment site.

The deployment was a somewhat anticlimactic affair. While I helped Xavier calibrate the recording equipment, Erin documented the whole thing. Kayley, a dive enthusiast herself and a recent WWU graduate, helped Rob into his dry suit. Kayla, a sophomore and the youngest member of the team, snapped photos from a safe distance. The hydrophone package was strapped to a yellow steel plate, which would keep it from shifting around too much on the ocean floor and make it easily visible to divers. Once we heaved the entire thing into the water using a pulley system, Rob went over the side to guide the equipment to the ocean floor and mark its location (and snap some photos – see below).

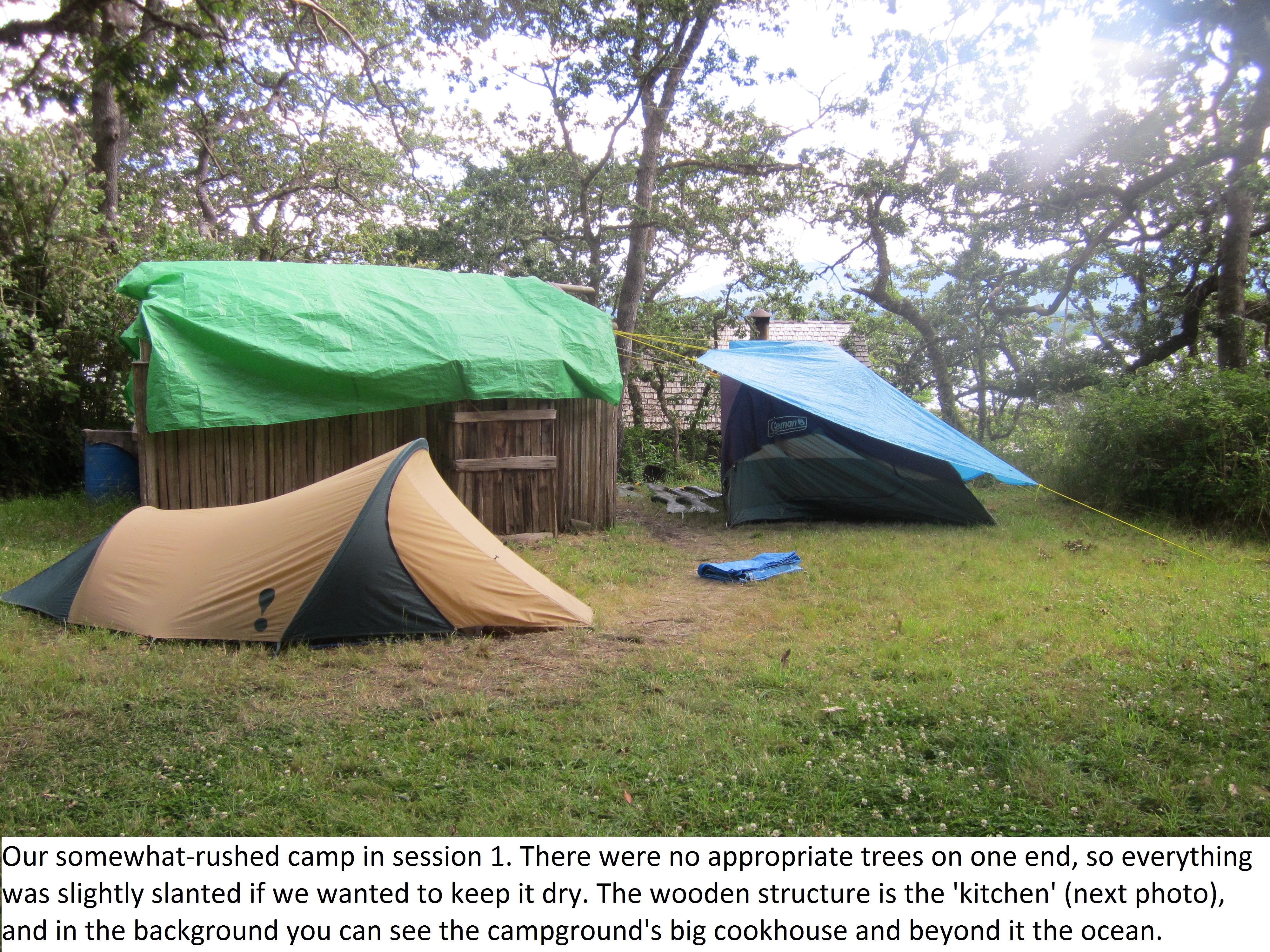

After returning to dry land, the interns and I headed half a mile up the road to our home away from home, the Heron Rocks Campground. This pristine piece of oceanfront land, owned and cared for by a cooperative of non-Islanders from all over Canada, is one of the loveliest campgrounds I’ve ever seen. The property is lived on and maintained by an Islander couple whose last name I never learned. Betty, a sinewy woman with a long braid of steel-gray hair and kind eyes, checked us in. Darryl, her distinctly elfin-featured husband, showed us around. Darryl and Betty have lived in the land for a number of years, playing host to the members and their families that come to vacation there each summer and keeping things tidy in the winter. Darryl, a certified jack-of-all-trades, maintains the land’s carpentry work, including the hand-built structures on every campsite that serve as a kitchen and living area, and the property’s dozen wooden outhouses.

We hastily made camp in a downpour, stringing tarps over everything in a fashion that made up for in redundancy what it lacked in skill and style (see photos below). Because it was only mid-June, we had the entire place to ourselves. After a trip to the island’s only general store for a celebratory six-pack, we proceeded to one of the property’s communal fire rings on the beach and roasted wieners while we watched the tide creep up on us. Upon exploring the campsite, we discovered that each of the lovingly-tended outhouses had its own name (including ‘The Coliseum’, ‘The Temple’, and the clifftop ‘Loo with a View’, which if you left the door open indeed provided you with a spectacular ocean view from your seat). Each loo also had a different information sheet posted to the back of the door, describing an aspect of the local ecosystems or wildlife. Kayley quickly made it her mission to ‘collect them all’, while Kayla and Erin devised ingenious ways to avoid being attacked by the ticks Betty had warned us about (notice the socks over pants hems in the photo – we saw only one tick in the entire season, and nobody got bitten). We went to bed that night before the sun went down, preparing for the next day’s adventures.

Stay tuned for Fieldwork Part 2 – Wind, Rain and Tall Grass, in which my session 1 team helps me refine my methods and we discover the best pizza on the Canadian Coast Guard’s menu!

Seals and salmon in Bellingham's downtown creek

Erin Matthews, undergraduate student

2 April 2015

I have been interested in pursuing a life as a biological researcher for as long as I can remember. I am majoring in Biology with and emphasis on ecology, evolution, and organisms and am scheduled to graduate June 2015. I chose to attend Western Washington University beginning in September of 2011 because of the many opportunities Western has for undergraduate research. I was hired as a field data collection assistant in 2012, my sophomore year, and my senior year I took over as manager of the project. I currently coordinate and manage nine research assistants.

Our research focuses on the predator and prey interactions of harbor seals and salmon in the Whatcom Creek estuary. My team and I make field observations at the creek, which is close to WWU campus, several times a week. We collect information on environmental conditions, such as weather and tide, we note human behavior and presence and make other general observations. When seals are present in the creek we record their behavior and photograph them. We are provided fish abundance and species data by the fishery at Whatcom Creek. We use the seal photographs and a wildlife fur pattern recognition software to identify individual harbor seals in order to compare the behavior of individuals to themselves and to each other over the several years that this study has occured.

We hope to answer questions about this system such as: how correlated is salmon abundance and the seal aggregative response? Do harbor seals prefer to comsume some salmonoid species over others? Do harbor seals tend to hunt alone or on groups in estuaries? Are harbor seals present the estuary year round or only during the salmon run? Do many individuals from the population eat salmon from the estuary or do only a few “problem individuals” consume most of the salmon from the estuary? How likely are the same individual harbor seals to return to the estuary to hunt for several salmon runs in a row?

In the coming year our findings will be presented at the North West Student Chapter for the Society of Marine Mammals conference, Western Washington University scholars week, and we intend to submit a manuscript for publication.