May 2015

Undergraduate Research Experience

Erin Matthews, undergraduate student

23 May 2015

I am am incredibly lucky as an undergraduate student to have been given the opportunity to be a filed research assistant on seal and salmon predator/prey interaction research. I specifically chose to attend Western Washington University because of the abundance of opportunities for undergraduates to get real research experience. As an incoming freshmen I imagined working closely with a faculty member, getting my name on a poster or (in my most optimistic dreams) a paper. I did not foresee managing a research lab project and nine of my peers.

About half of my assistants were already volunteers when I took over as project manager last summer, the other half were hired and trained by me. I have learned a lot about working as a team and how to organize people. Here are some examples:

- Asking a team of busy college students to come in and work at their convenience is no where near as effective as making a schedule

- Creating and posting a "to do" list helps everyone understand what is going on with the project and helps the team works more efficiently

- Time spent making a detailed and organized field sheet in excel saves quite a bit of time later interpreting and entering field data into the computer

- It's a good idea to remind your team to dress warmly and also to pack extra gloves in the field bag

In the past year my team and I have entered years of data, organized thousands of photos, and conducted a significant amount of data analysis. It would have been impossible for me to make the progress on this project that has been made this year without my team. It has been a pleasure working with my assistants so far and I am looking forward to another summer of data collection and data entry.

P.S. We are hiring

The NWSSMM Conference

Ashlyn Teather and other undergraduate students

23 May 2015

Things have been busy here at Western for the undergraduates and graduate students in the lab! The arrival of spring quarter means it is time to start presenting some results of our research. The big event of this month was the annual meeting of the Northwest Student Chapter of the Society for Marine Mammalogy (NWSSMM for “short”). The meeting was held at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon on Saturday, May 2nd.

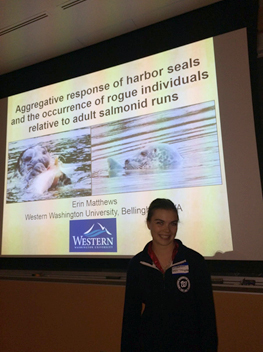

The purpose of this meeting is to allow students of the Pacific Northwest studying marine mammals to meet, interact, network, and discuss their research with each other and some faculty. The day was mostly full of 12-minute presentations from graduate students (and our Erin Matthews, one of two undergraduates who gave a talk!), broken up by much-needed breaks for coffee and snacks. Lunch was followed by a 45-minute poster session at which Sara and Ashlyn shared their work along with other undergraduate and graduate students.

The day kicked off with a keynote address from Dr. Ari Friedlaender, who spoke about his work in spatial modelling and gave us a tantalizing look at the state-of-the-art technology he and his students use to model whale movements underwater, including a program that reminded Kat of Roller Coaster Tycoon, but with a cartoon whale instead of screaming tourists. Dr. Friedlaender also extended some advice to all the students in the room about getting into and making the most of graduate school.

One of the things that was new to the conference this year was a professional panel held after the poster sessions. Instead of launching back into talks while everyone was still working off their post-lunch drowsiness, OSU put together a panel of some of their professors and technicians that study marine mammals, and opened the floor to questions that students wanted their opinion on. The panel included Dr. Friedlaender, Dr. Markus Horning, Dr. Leigh Torres, and faculty research tech Sharon Nieukirk (standing in for Dr. David Mellinger and admirably rounding out the sex ratio).The panel discussed everything from the correct application of new technology, to how they choose graduate student applicants, to the harsh realities of being a woman and/or having a family in an academic career track.

Oregon State’s Marine Mammal Institute put on a fantastic conference, and it was great to learn about everything happening in the world of marine mammals around us. Special thanks to the ORCAA (OSU's Research Collective for Applied Acoustics) lab for their dedicated work, and for Miche Fournet and others for allowing us to stay in their lovely abodes (and play with their puppies and baby chicks). Take a look at the pictures below to learn some more about how our day went!

Dan models before presentations started. Undergraduate and

graduate students, at any level of research, are

invited to the conference!

Sara, Allegra and Ashlyn stand near their posters at the

conference. Sara and Ashlyn got to chat with many

professionals in the field to get feedback on their work and new

ideas for future work.

While Sara and Ashlyn presented posters at the conference, Erin

gave a talk about her research!

Harbor Seal Genetics Research

Sara Spitzer, undergraduate student

22 May 2015

Hello, my name is Sara Spitzer. For a little more info about me, you can check out my blog entry for the month of April. For this blog post, I want to talk about my research (which is super awesome, in my very biased opinion)!

I started working on the seal genetics project in Fall 2014 and am quite close to finishing, which is ridiculously exciting! I meet individually with Alejandro every week to discuss my progress and any other topics relevant to the research. Alejandro is my advisor on the “communications” side of the project. He’s helped me write a grant proposal, guided my research for the manuscript we will be writing this summer, and edited my abstracts and poster for Scholars Week and the Marine Mammals Conference earlier this month. Dietmar Schwarz is my advisor on the lab side of the project. He taught me qPCR, I use his lab materials, I let him know when we are low on supplies, and I consult him when I have lab-related issues or questions. Needless to say, I’ve learned a great deal these past 7 months about how to manage and troubleshoot a research project, as well as how to collaborate and communicate with others in the lab, which I think are invaluable skills that will serve me well in my career as a scientist.

My research involves using genetic methods to determine whether diet preferences vary between male and female harbor seals. Seal scat was collected from 2 haul-out sites in the Georgia Strait during the harbor seal breeding season (May-Oct) in 2012 and 2013. Austen Thomas, a former WWU student and current PhD student at University of British Columbia, used a genetic method on the scat called DNA barcoding to determine not only the species of prey consumed, but also the proportion of each species present in the diet. This method is ground-breaking because traditional methods for diet studies cannot determine the proportions of each prey item, but ours can. The work I’m doing for this study is to take these scat samples and determine the sex of the individual that deposited them. I am using a technique called qPCR, which has been shown to be an effective way to amplify target genes from low quality DNA, such as scat DNA. I look for a gene that codes for a zinc finger protein on the X-chromosome (ZfX) and a gene that codes for a zinc finger protein on the Y-chromosome (ZfY). We use the ZfX gene as a control because ZfX should be present in all individuals. Therefore, if the ZfX gene does not amplify, we know that the DNA is either too degraded, too dilute, or that something went wrong with the reaction. Intuitively, the presence or absence of ZfY will tell us whether the scat is from a male or female.

We have some preliminary results! We have complete data from one haul-out site (Comox, Canada) in 2012 and 2013. The data were strikingly consistent between years. Females consistently had a greater variety of prey species in their diet than males. Males and females ate similar amounts of Pacific Herring, but males consumed far more salmon than females, especially Chinook. However, we know that abundance of fish species plays a role in diet proportions. Pink salmon run every other year (ie they spawned in 2013, but not in 2012). In 2013, pink salmon made up almost 50% of the salmon consumed by both males and females. In 2012, however, pink salmon was less than 20% of the total salmon consumed by males and females. I’m almost done with the 2012 and 2013 data from the second site (Cowichan Bay, Canada) and we’re excited to see whether these trends remain consistent between haul-out sites.

There are limitations to our study. We know what males and females are eating, but we don’t know why and we cannot answer this question with the data we currently have. It could be that males and females have different energetic needs and therefore consume different species in different proportions. It is for this reason that we will examine nutritional data for fishes to determine if females are eating nutrient-dense fish during the breeding season. Another hypothesis is that females are restricted to foraging around the haul-out site during the breeding season, so they must eat what they can find. Males, however, are not restricted to the haul-out site and therefore may be more selective with their food choices. Future research where our diet analysis can be paired with foraging data gather from tagged individuals could help us answer the question of why male and female harbor seals are eating different things.

Fieldwork Part 3 – Session 2: Girl Power

Kat Nikolich, M.Sc. student

21 May 2015

My last few blog posts have been an accounting of the highlights of my field work last summer on Hornby Island, BC, where I spent six weeks camping with three different teams of undergraduate research assistants (see Fieldwork Parts 1 and 2). The first session ended the last week of June, and three weeks later I was back at it with a brand new (almost) set of interns. Late July/early August is the height of visitor season on Hornby Island, and along with that came some interesting challenges. Among those challenges was a theme that I would like to address: the public perception of women in science.

This time, my interns arrived on the ferry from Anacortes. Erin, one of my assistants from session one, was returning for another trip. When I asked her candidly if she was glad to be back or secretly dreading the next two weeks, she told me honestly, “A bit of both.” With Erin this time was Elizabeth, one of my Ecology students from the previous fall. Capable and hardworking, Elizabeth is very opinionated and wears her emotions on her sleeve. Amy, my third assistant, was also a past student of mine. At nineteen, Amy was the youngest person I took into the field; despite that, she is mature beyond her years. Small, blonde and athletic, Amy looks like the Southern California bombshell that she is.

None of the four of us were what you’d call ‘powerfully built’, but there was enough attitude in this group to fill a gymnasium. This first became apparent to me on the long and cramped trip north. By the time we caught the first ferry (on time for once), I was uncomfortably aware that these ladies were a far cry from the laid-back group of the first session. Warnings from my friends flew through my mind: “You’re going to take three girls to the wilderness and make them live together? Good luck!” or “Girls are so catty and competitive. You should take guys instead – they’re much easier to get along with.” I quelled these voices, determined not to let their sexist mantras poison my thoughts. An all-woman field team had never been a problem for me before, and it wouldn’t be a problem now. We’d all just need to schedule some alone time, and be professionals.

This picture about says it all. The session two ladies (Amy,

Erin and Elizabeth, left to right) at the

Denman Island ferry terminal, three hours into the trip.

When we drove onto Hornby, I felt instantly as though I’d never left (I was unsure whether this feeling was comforting or wearisome). We made the short drive to Heron Rocks, where we were greeted by the wonderful caretakers with gifts of fresh fruit and homemade mead. Because the land is a cooperative, first priority of camp sites goes to the owners. As a lowly visiting researcher, my application was nearer the bottom of the pile. This resulted in my group’s time being split: our first week would be spent in the Gate Cabin, a lovely little bungalow complete with four pallet beds, a kitchen area with dishes, comfy chairs, a private outhouse (unnamed, though we came up with some ideas) and in-wall electricity (ideal for charging our equipment). For the second week, we would move to a tenting spot.

The interns were at first excited about living in a cabin instead of a tent, but after a few days their illusions began to shatter. The first inconvenience was the noise factor. In the first session, I would get up early each day and quietly make coffee for the interns before they awoke. The small cabin, however, has cathedral-caliber acoustics. I quickly learned that my early-morning rustlings resulted in grumpy (but caffeinated) interns, so after the first few days I switched to doing all of the cooking outside on our gas stove anyway. The second issue was that, despite having a sink, the cabin had no running water. We were provided with a trio of five-gallon water jugs that could be refilled at the tap, the closest of which was a quarter mile down the hill (uphill on the way back). This was the first time that I wished I had some males around, but I was determined that if a man could carry an unwieldy 45 lb jug up a hill, then so could I. The first time I went to the tap, some concerned campers offered to help me. I wasn’t really struggling, so I waved them off. The second time, I tried two bottles at once. That involved some sweating and swearing, but it turns out that carrying heavy equipment every day had done wonders for my strength. It wasn’t until the third refill that I discovered the wheelbarrow leaning up against the cabin’s back wall, and felt like a huge idiot.

Home sweet home for the first half of session two. Note the red

wheelbarrow in plain sight to the right.

Photo by E. McMurchie.

The other downside was that the cabin was about as far from our observation site as it was possible to be, which meant carrying our burden of hip-waders, theodolite and other gear three times as far each day, past twice the number of campsites. We needed to be very quiet in the early morning, and very sneaky later on in the day when going for breaks. Because it was high season, there was not an empty spot in the place, and everybody wanted to talk to the researchers. After the third time that forced politeness led to interns being late for their shifts, we were forced to plan our routes carefully to avoid the chattier campers. Don’t get me wrong – I think it’s fabulous that people took an interest in my research. I had prepared the interns to answer questions and chat with people about what we were doing and why, as I believe that one of the key components of any field work should be public outreach. To that end, I put on a public talk each time I was on the island, and encouraged campers to come and get all the details.

The first session wasn’t as crowded, so I was sorely unprepared for the public onslaught of session two. In fact, we achieved a sort of celebrity status around camp: we became known as the ‘seal girls’. This label was often accompanied by a silent but apparent prefix. You could tell from somebody’s tone whether we were the Crazy Seal Girls (what kind of young women want to sit on a rock and stare at seals all day instead of getting a real job and/or a husband?), the Cute Seal Girls (how adorable, do you remember being that young and vivacious?), the Mysterious Seal Girls (what’s all that equipment for? Are they secretly working for the government?), or the Annoying Seal Girls (I wish they’d stop clanking by my tent at 6am!). It was never the Smart Seal Girls, the Professional Seal Girls, or the Strong, Competent Seal Women, despite the fact that I would describe every member of my team thus. Only the very few people that took the time to get to know us really thought of us as Scientists, not Girls.

Amy browsing the wares at the Free Store. Settling down with

children doesn’t seem to be her thing,

but even if it was, she would still be a strong woman of science.

Right, Amy? Photo by E. McMurchie.

Everyone else clearly took us to be a quaint source of amusement at best, and a source of irritation at worst. This came through most strongly when folks would come upon while surveying and ask what we were up to. Although we were obviously working, and busy, these folks believed that we could put it all down to chat with them. Whatever it was that four young women in shorts and t-shirts were doing on this rock, it couldn’t be that important. While I appreciated the interest, and we did our best to answer any questions, this obvious lack of respect for our work grew to be source of unease.

This all came to a head on one of our last days of surveying. It was really busy, and when I spotted an older gentleman coming up behind us I prepared myself for the inevitable interruption. But this man just started to laugh: that overly-loud, fake kind of laugh that people do when they’re being unabashedly derisive. The man slapped his knee and gestured to his wife. “Come here, honey,” he roared. “Look at this! These girls are sitting here getting paid to watch boats! How ridiculous!” Seething, I put on a smile. “I’m glad you find this amusing, sir,” I told him, hoping he’d go away. But he ignored me, continuing to talk about us as though we were specimens behind glass, or perhaps deaf. Not once did he ask us what we were there for, or why. He assumed that a) we were somebody’s hired help, b) we were doing something pointless and silly, and c) that he could talk at us like we were made of stone.

Admittedly, this man (for lack of another blog-friendly term) represented an isolated incident. However I’m willing to bet that if he came upon a similar group of men our age, his reaction would have been very different. In session three, when I had male field assistants, people would often come up and immediately turn to one of the guys to ask what kind of surveying we were doing. When it was pointed out that we were in fact biologists and that I was the one in charge, these people realized that they’d assumed men were in charge, because of the fancy equipment. At least they had the grace to look flustered.

Back at camp, things were much the same. When we moved from the cabin to the tent site, I did most of the moving during one of my surveying breaks. A gentleman in the next camp watched as I erected our tent and began to string up a tarp over the kitchen lean-to. He ambled over a couple times, not to offer his help, but to offer advice. In fact, this man turned out to be a fount of unsolicited information on how to drive, how to change the batteries in my equipment, and how to read my tide charts.

But despite this, we held up fairly well. While I was correct in assuming that our personalities didn’t all mesh, the field session did not dissolve into female hysteria. We collected some top-notch data, and our forced time together surveying was spent making up stories about what we were seeing. By the end of the trip, we had concocted a long and complicated soap opera involving a lost Stellar sea lion who fought against the dominion of the 2500 lb. mafia boss who ruled the haul-out. Meanwhile, the seals were all mid-level participants in an illicit smuggling scheme devised by the skipper of a very distinctive red rental boat that we referred to, uncreatively, as Lund.

Our antagonist Lund, off to steal the beguiling innocence of

our seals. Photo by E. McMurchie.

Throughout the biological field work I’ve been involved in, 95% of the participants have been female. And despite the insidious pervasion of gender stereotypes, I wouldn’t really have it any other way. Women bring an aspect to science and field work that I dare not define but that I certainly appreciate. The women I’ve worked with in this field, from the SAPPHIRE project in Hawai’i to my work on Hornby Island, have all been among the cleverest and most impassioned scientists I’ve had the pleasure of calling friends. As members of a sisterhood, we have embraced feminism and femininity equally, and I believe the field is better for it.

So here’s to not having to act like a man to do a traditionally male job, and do it well. Here’s to painting our nails to cover the dirt, drying our lacy knickers on a helicopter pad, and washing our long hair in a bucket. Here’s to passive aggression, laughing through tears, and dressing for the perfect tan lines. Here’s to women in field biology. Girl power all the way.

Session 3 hard at work doing great science. Thanks ladies – you

taught me not to give up.

Seal research in Bellingham: An introduction to the background and happenings of the Bellingham Harbor seals, and myself

Daniel Woodrich, undergraduate student

1 May 2015

Sometimes, finding something common in an unexpected place is as wondrous as finding something uncommon exactly where you expect it. Although Whatcom creek has an estuary section that is not far from the bay, it is hard to contain excitement upon spying the first seal head pop up from beneath the surface of the creek. As researchers who stand on alert for hours on end in order to witness such sightings, we are often privy to the joy and surprise of the passers by who witness the seals in the creek for the first time. Only during some points of the year is the presence of seals surprising to our team of researchers. Harbor seals often enter Whatcom creek for a very sensible reason: the chance to hunt salmon that are returning to the hatchery or tributaries to Whatcom creek in order to lay eggs after years out at sea. This seasonal presence is expected, yet some seals choose to return when no salmon are in the creek at all. These “rogue seals” carry interesting questions about seal behavior. Are the rogue seals the same individuals, time after time, or year after year? Are they there for any discernable reason? These questions, as well as the questions posed in Erin’s post, are what our research group seeks to learn more about.

The seals that enter Whatcom Creek are no mystery to the fishermen that compete with the seals to catch the same salmon during the fall season. The seals have a notorious reputation of stealing fish off the end of fishermen’s line: a behavior oft spoken of, yet seldom witnessed. Some fishermen have identified particular seals as repeat offenders. Seals are smart hunters, and their effectiveness has historically made them the enemy of the fishing industry. Harbor seals in the state of Washington used to be the subject of a bounty program that reduced their numbers, in order to reduce their consumption of commercially available fish. The termination of this program, as well as the introduction of the Marine Mammal protection act has brought the species back to stable levels in the region.

I was privileged to start working on this project in the summer of 2014, along with a second seal project that takes place on the Bellingham waterfront. Many Bellingham residents can notice the large “HORIZON LINES” ship perpetually sitting at rest in the bay from a vantage point on the west side of Sehome hill: a keen eye may notice the frequent presence dark blobs strung out along the narrow log boom that extends along a small inlet to the right of the ship. Here, adjacent to the chemically contaminated section of the waterfront, many harbor seals rest, socialize, and rear pups. The seals make frequent use of this site despite the activity of the nearby industry, the boats that frequently pass through the waterway, and the noise from the railroad. As far as real estate goes, these factors might seem to devalue the area to the seals, so we monitor the presence of seals and their pups to track their responses to the human environment around them. This site may be on track to see extensive development in the coming years, so long term abundance data will be very useful to monitor the effect of human impacts.

I feel lucky to live in a place where these marine mammals inhabit our backyard. Next year I am excited to be taking over the management of the Whatcom Creek seal research project. Both of the projects I described are long term, so there is greatly valuable data to analyze that extends beyond the duration of the tenure of a single undergraduate manager. Before taking over the project, I will be interning this summer in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to help in efforts to track the extremely endangered North Atlantic right whale population. This internship is a component of a scholarship that I received called the Hollings scholarship, which is a scholarship sponsored by NOAA geared toward distinguished students across the country in fields pertinent to NOAA’s mission. I was encouraged to apply to the scholarship as a sophomore by the fellowship office at Western, and I am one of four students in my class at WWU who made it into the program. I would love to end up in a career related to marine mammal ecology, and I am very grateful for the opportunities presented and developed by the faculty at Western to help me work towards that goal.

Fieldwork part 2- Session 1: Wind, rain and tall grass

Kat Nikolich, M.Sc. student

1 May 2015

If you’re just tuning in, I’ve been telling stories about my field work in Canada last summer on Hornby Island (see Fieldwork Part 1 – The beginning). I left off last time when my session 1 interns and I got to Hornby Island and set up camp. The next morning and started out across the beach to find the perfect place to survey from. With the campground attendant’s warning about ticks in the tall grass echoing in our minds, we all suited up with long socks over the hems of our pants, long sleeves and popped collars – bring it on, bloodsucking ectoparasites! We traipsed along the grassy cliff overlooking the seal haul-out to find a good vantage point. After an hour of this, we were sweating in our tick-proof layers and were uncomfortable with the idea of hiking that far every day.

We decided the ideal spot was Toby Island. When you first look at this pinnacle of rock at the far point of the bay, you wonder why it’s called an island at all. At low tide, it looks like a continuation of the beach. However, there is a five-meter tidal difference at Hornby Island. Toby, as we quickly discovered, can go from being part of the beach to being separated from it by a channel of water up to five feet deep in about 70 minutes. I had come prepared for tide: I had a pair of hip-waders for each person on the team. I didn’t come prepared with a boat, so tide was going to be a factor in when we could survey. Nevertheless, the sometimes-island had a good height vantage over the seal haul-out and was easy to get to from camp. And the best part? There was only a small patch of tall grass on it! We were sold.

After a quick lunch, the interns (Erin, Kayla and Kailey) and I headed up to Toby Island with all our equipment: a thirty-pound theodolite, the theodolite’s tripod, three folding canvas chairs, a dry bag containing a laptop computer and a GPS, a pair of binoculars, and a pop-up canopy in case of rain. Between the four of us, we managed to haul this load down the beach to the island. The first day was a test day: I had a good idea of how I wanted to survey, but it was open to re-evaluation. After finding the ideal place to set up the theodolite (a surveying instrument that we used to get accurate compass bearings on our sightings and high-magnification views of the haul-out), I sat down to supervise the team while they got familiar with the theodolite, reticle binoculars, and the spreadsheet on my little laptop to record data.

After a few false starts, we revised the surveying protocol so that everybody was satisfied. It went like this: at any given time, three out of four team members were surveying and the other had a break. Each surveyor had a certain job, and every two hours we would rotate. At the start of each hour, we would record current weather conditions and spend the first five minutes of each hour counting seals in the area. The person on the theodolite would scan the rocks while the person on binoculars would scan for seals bobbing in the water. These were reported to the person on the laptop. After the seal count, we counted the boats in the area and proceeded to spend fifteen minutes ‘marking’ them all (getting a compass bearing and distance to the boat using our equipment). After that fifteen minutes, we went back to counting seals. After three repetitions of seal count/boat survey, we were back at the top of the hour and did it all over again.

As prepared as I was, there were a few eventualities that I wasn’t prepared for, and my interns saved the day. I had not anticipated my laptop battery only lasting five hours, while the surveying day could be up to twelve. Kayla had the idea to use a notebook for a few hours a day while the laptop recharged back at camp. I also hadn’t thought about how heavy all that equipment was to carry back and forth every day. It was Kailey that suggested we just leave some of it out on the island permanently. We wrapped the chairs, canopy and theodolite stand in an old tarp and dragged it into a tuft of tall grass. It looked, we concluded, like a badly-hidden dead body, dumped by a group of very lazy murderers. As such, it was left unmolested for the whole two weeks.

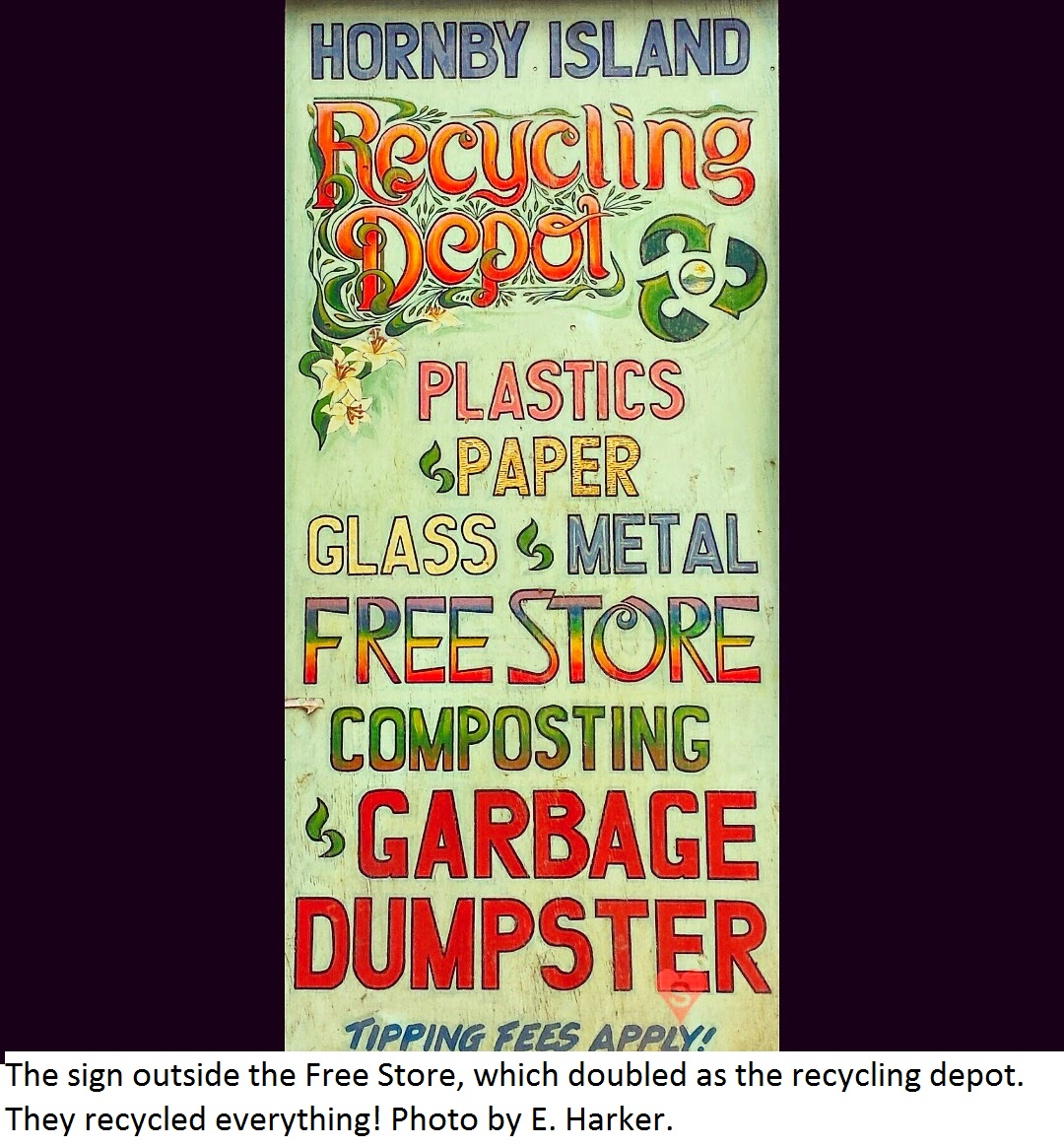

We had come prepared for June weather in the outdoors. We hadn’t anticipated that we would choose the windiest spot in the Northern Gulf Islands as our survey site. At camp, it averaged about 22° C during the day. On Toby Island a quarter mile away, the onshore winds left it feeling more like 12°. Thankfully, Hornby Island has a Free Store. Picture a garage sale meets Value Village. You can find everything from spare bike parts to mattresses to clothes and toys in this one little building, and everything is free. We stocked up on gloves, sweaters, toques and blankets, and felt ready to face the weather with impunity. It turns out that no amount of layers can prepare you for sitting for six hours at a time with a cold wind blowing in your face.

After the first couple days of surveying, we settled into a routine. I would get up before everyone else and make coffee with which to coax my cranky interns out of bed (because it was midsummer, the days started at dawn, around 5am). After a quick breakfast of oatmeal or cereal, myself and two interns would head out to begin surveying. We would survey for twelve hours, or until the weather got too bad, or until the tide started to rise too high to wade through; whichever came first. We then headed back to camp and I would cook a big hot meal. After dinner, we took time to explore the beach for tidepools, read a book, or take a walk to the nearby marina. The marina boasted a corner store, cafe and, most importantly for the girls, a Wifi hotspot. The café doubled as a pizzeria, and my friends in the Canadian Coast Guard tell me that Coasties patrolling in the area will go out of their way to put in at Ford’s Cove just to grab pizza – it’s that good.

When I talk about field work, people ask me, “Do you really just watch seals for twelve hours a day? How do you keep from going mad with boredom?” My answer to that is complicated. Most of the time, we were actively doing something (counting, marking or recording). When there were lots of boats and seals, the time would fly by. However on inclement days, there would be very little for us to record. It was during these times when a fifteen-minute boat survey would take us two minutes to complete, and thirteen minutes were spent sitting around waiting. To pass the time and keep our minds off the cold, we talked. After the first few days we had exhausted the usual safe topics like our families, favourite TV shows and discussions about school and work. It wasn’t long before we knew all the gory details of each other’s love lives, health history, political views and childhood traumas. In my experience, this is how it goes in the field. When you live and work with a small group of people 24/7, you get to know one another fairly intimately. After two weeks, we were all craving some alone time.

On the day we packed up camp, it felt surreal – especially because I would be back in three weeks. The short ferry trips and ride down Vancouver Island went by quickly, and after my interns were safely on the ferry back to the mainland I took a deep breath and realized what I’d just successfully accomplished. We had collected great data, and had all made it back with no injuries, tears or tick bites. I looked down at my filthy clothes, sat down on a pile of my filthy camping gear, and laughed myself silly. One trip down. Two to go.

Stay tuned for Fieldwork Part 3 – Session 2: Girl Power